news

Getting started with inclusive design

How to make inclusive design a thoughtful beginning, not an expensive afterthought.

Maddie Collings

Service Design Lead

How to make inclusive design a thoughtful beginning, not an expensive afterthought.

Maddie Collings

Service Design Lead

Published: 13 August 2025

Too often, in the mad rush to launch a product or ship a new feature, inclusive design and accessibility considerations become an afterthought.

A ‘checkbox’ activity. A backlog item. A quick once-over to ensure compliance with Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG).

Despite our best intentions, this causes technical debt, leads to rework, and perpetuates the growing digital divide in our society.

It’s also a missed opportunity.

To design truly accessible and inclusive digital experiences, we need to rethink the design process.

A lot of designers have been trained to ‘design for core users’ not ‘edge cases’. I believe this is a flawed approach that encourages personal bias to creep into our designs.

As a digital designer, keeping on top of industry best practice is critical. It means I always take a ‘digital-first’ approach.

But my tendency to think ‘digital first’ when designing, if left unchecked, can unintentionally exclude people.

This is where inclusive design practices are helpful.

Every time I speak to someone who has unreliable internet, struggles with a small screen, or needs a grandchild to help them set up a new app, it’s a reality check — a powerful reminder to step outside of my bubble and consider diverse user needs.

When you do this and design with diversity in mind, your solutions can reach more people than you expect.

Look at curb ramps on your footpath.

In the 1970s, Michael Pachovas and fellow disability advocates poured cement onto a Berkley footpath in the United States to create a ramp.

The makeshift ramp was an act of defiance. A greatly needed one that gave his community something they’d never had before: access.

But it wasn’t just individuals in wheelchairs who benefitted.

Suddenly, the footpath became accessible terrain for parents with prams, travellers with luggage, trades and delivery people pushing carts and heavy equipment, and even skateboarders and joggers.

It’s known today as the curb-cut effect.

The belief that designing for people who are under-represented and often excluded will benefit all of society.

It starts with a mindset shift.

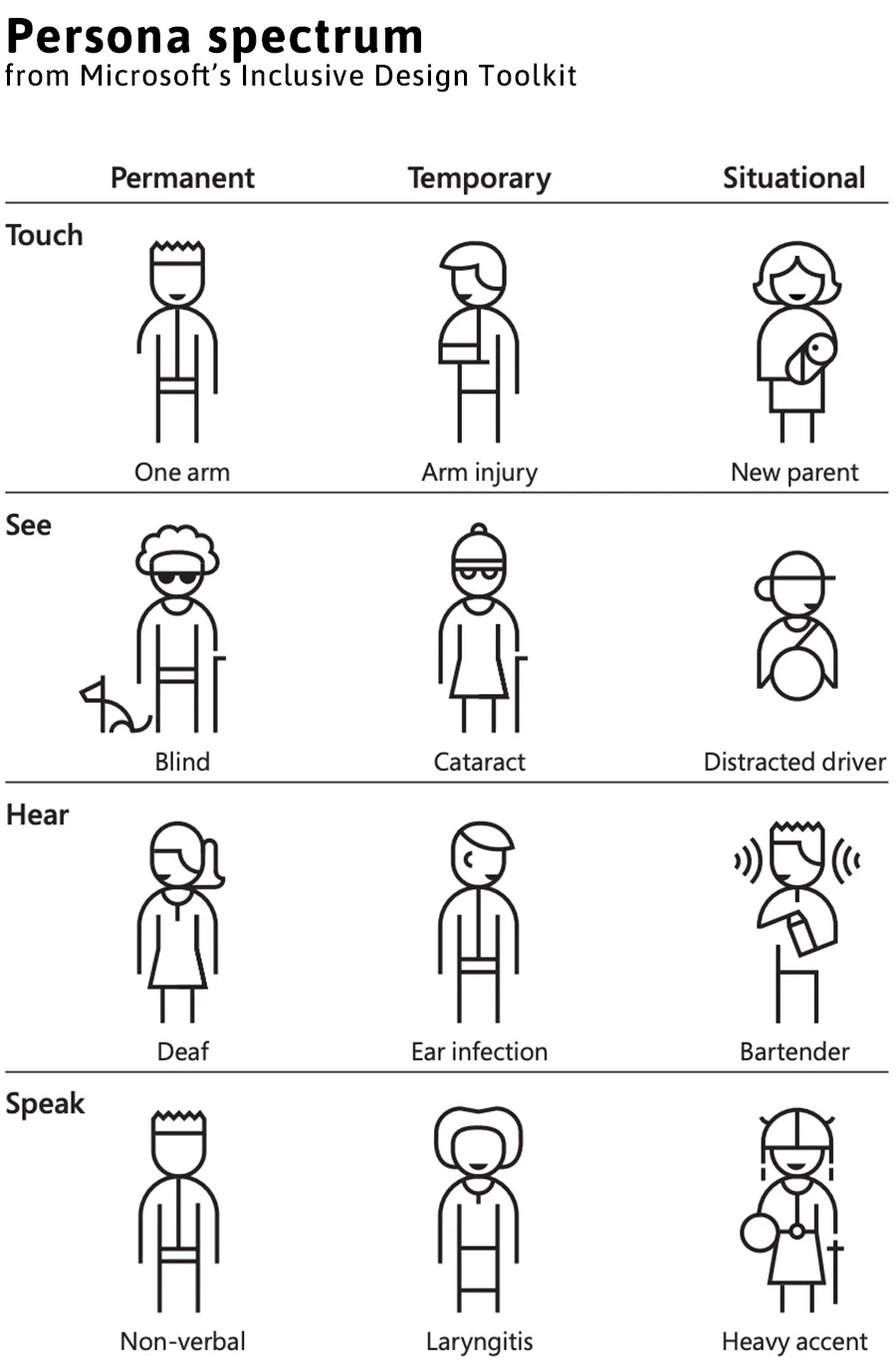

We need to stop seeing disability as only fixed or permanent. And instead realise that disabilities sit on a spectrum and can be temporary and situational.

Microsoft’s Inclusive Design toolkit illustrates this beautifully. (It’s also an incredible resource I’d encourage you to use!)

Suddenly, ‘edge cases’ are no longer ‘edge’.

And we start to realise just how many people we can reach through inclusive design practices.

Because the reality is, we’ll all at some point (or various points) in our lives face barriers when interacting with the world.

So how can we design in a way that lowers those barriers?

Where do you start?

As outlined within the Digital Inclusion Standards, it’s important to consider diverse user needs from as early as the discovery phase. This reduces design bias early on and ensures all user needs are addressed.

It’s an approach we recently took for a Federal Government client whose digital product is used by millions of Australians.

The client wanted to test early concept designs to make sure they were designing an inclusive product that met diverse user needs, particularly for Australians who were more vulnerable.

Instead of thinking of vulnerability and diversity purely in terms of demographics like age, gender, cultural background, and geography — which we felt was too narrow — we took a contextual approach and asked: What real-world scenarios increase vulnerability? And how does this impact the way someone might engage with a digital product?

It led us to recruit participants who have:

We also made sure we were recruiting people who were often underrepresented including people with disability, First Nations and carers.

Hearing from these participants was eye-opening and deeply humbling.

I’ll never forget how one participant told us this one tiny feature (which we had dismissed as unimportant) was a gamechanger for her.

It forced us outside of our own biases and stretched us to design for these real-world scenarios. It also gave us a rich, nuanced understanding of how people actually interacted with the client’s prototype – which was a goldmine for ideas and paths forward.

For Australia’s National Disability Data Asset, we included user feedback, research and testing at every stage of the design and implementation of the website. By having these feedback loops throughout, we got to appreciate the full spectrum of accessibility tools and navigation approaches used by the disability community.

We realised early on that no two experiences are quite the same.

Participants used accessibility tools based on their own unique needs. This included everything from screen readers reading at 2x speed, screen magnification at 64x the standard size, and users navigating content through menus, browser buttons, breadcrumbs and anchor links.

While no two experiences were alike. One theme was clear: Many people with disability develop workarounds to interact with digital spaces at considerable time, effort and cost to them. When these digital spaces don’t work for them, they abandon them, instead turning to their networks for information and support.

It highlighted just how important the co-design process was.

Together with users, we designed easy to read content, meaningful labels and consistent visual cues, so users could navigate the site with ease and confidence.

Co-designing with users is an approach I’d love to see become the norm in digital design.

As a volunteer ski guide, I help skiers with disabilities learn how to confidently get down the mountain. Some have low vision, others might be neurodivergent or have cerebral palsy. Depending on their abilities we use adaptive equipment or come up with a system to ski down the slopes together.

Watching someone light up as we rush down the mountain together reminds me just how powerful collaboration and inclusive design can be and how it can open up new experiences for people who might otherwise be excluded from snow sports.

These days I still take a ‘digital-first’ approach. But for me, ‘digital-first’ has taken on a new meaning.

It’s not just designing digital experiences that are accessible and inclusive. It’s thinking holistically about the user experience and designing for diverse needs — which should include non-digital experiences that integrate with digital ones.

So, if people need to call a helpline, they can. If it’s easier to visit a support centre and talk to a human, it’s simple for them to do. If they prefer a physical card or paper-based form, then that’s available too.

This is something I need to continuously remind myself of, as a bit of a perfectionist.

As new services and products are launched, it’s important to celebrate the wins, but keep looking ahead to what the next version could be.

We help clients set up feedback channels and processes that turn customer insights into action. By creating continuous feedback loops, teams can test ideas with diverse users, learn what works, and keep improving. It’s all about testing, refining, and repeating.

Designing in an inclusive way is as simple as fuelling your curiosity and listening to different voices and perspectives.

By doing this early and often, you can challenge assumptions, feed creativity and design more inclusive experiences.

I’d love to see inclusive design move beyond a checkbox exercise — shifting it from an expensive afterthought towards a thoughtful beginning.